A Man among Other Men examines competing constructions of modern manhood in the West African metropolis of Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire. Engaging the histories, representational repertoires, and performative identities of men in Abidjan and across the Black Atlantic, Jordanna Matlon shows how French colonial legacies and media tropes of Blackness act as powerful axes, rooting masculine identity and value within labor, consumerism, and commodification.

Through a broad chronological and transatlantic scope that culminates in a deep ethnography of the livelihoods and lifestyles of men in Abidjan's informal economy, Matlon demonstrates how men's subjectivities are formed in dialectical tension by and through hegemonic ideologies of race and patriarchy. A Man among Other Men provides a theoretically innovative, historically grounded, and empirically rich account of Black masculinity that illuminates the sustained power of imaginaries even as capitalism affords a deficit of material opportunities. Revealed is a story of Black abjection set against the anticipation of male privilege, a story of the long crisis of Black masculinity in racial capitalism.

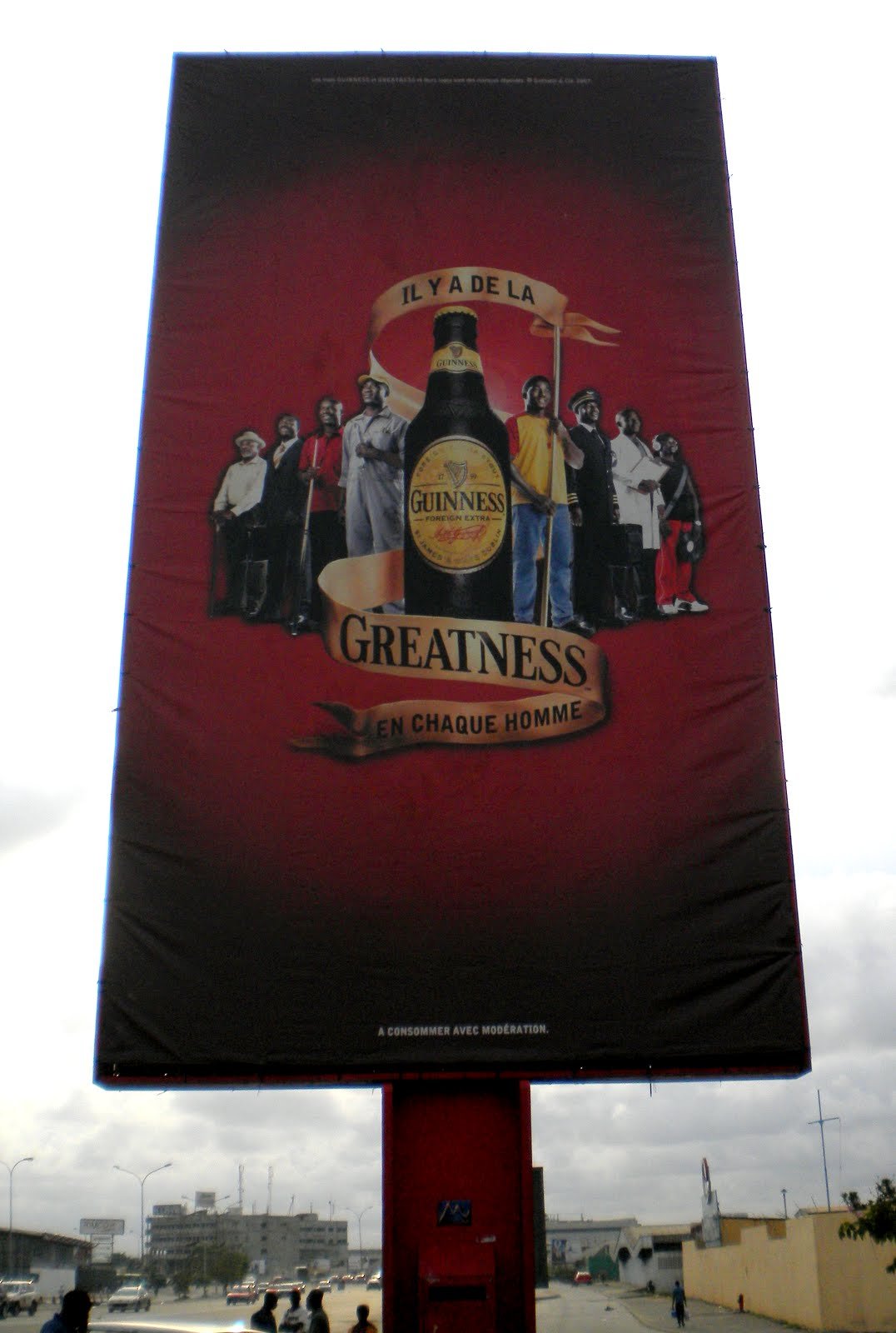

Introduction: Greatness in Each Man

Pont Général de Gaulle is a bridge that connects Plateau, Abidjan’s center and proud bastion of wide, leafy boulevards and steel-and-concrete modernity, with Treichville, the city’s original African district, or quartier populaire, following the segregated spatial logic of the colonial city. Treichville is named after Marcel Treich-Laplène, early French explorer and first colonial administrator of Côte d’Ivoire. Like Treichville, scattered throughout Abidjan are roads, bridges, and neighborhoods that preserve the appellations of the colonial era. Unlike those postcolonial states that indigenized the naming of their quotidian urban spaces, in Abidjan durable affirmations of European influence and the decades of Françafrique that dominate political, economic, and cultural relations between ex-colony and metropole endure. Pont Général de Gaulle honors Charles de Gaulle, the president of France when Côte d’Ivoire gained its independence. Côte d’Ivoire, the “Coast of Ivory,” alludes to a resource of brilliant whiteness whose violent extraction of bone from flesh is now firmly coupled with the dark side of the global economy. Yet Côte d’Ivoire’s most forceful assertion with respect to its name has involved not this association, but rather the maintenance of an unyielding Frenchness: it declared, in 1986, a refusal to recognize any translations of its name—the English Ivory Coast, the Spanish Costa de Marfil—in formal diplomatic exchanges.

After reaching land in Treichville, Pont Général de Gaulle arrives at the Jardin Bourse du Travail, translated roughly as the “Labor Exchange” or “Labor Placement” Garden. Crossing this bridge in 2008, one would have looked up to find a billboard advertising the Irish beer Guinness. Eight Black men stand on either side of a man-sized Guinness bottle. The label reads, in English, “Foreign Extra.” Each proud and distinguished looking, the men from left to right appear to be, first, a retiree, invoking a lifetime of steady work and a pension in old age, followed by men whose sartorial expressions suggest various accumulation strategies: a businessman, an athlete, a mechanic, a man whose casual T-shirt and jeans indicate no discernible trade, a pilot, a doctor, and a DJ. The man in jeans holds a banner declaring, Il y a de la GREATNESS en chaque homme (There is GREATNESS in each man). Unlike the obdurate Francophonie of the name Côte d’Ivoire, here the roots of greatness bow to an Anglophone foreignness.

That the average man whose work is unmarked bears the banner for all men illustrates how Guinness has tapped into an African predicament of jobless men. A validation, this advertisement lays claim to parity among men irrespective of work, when otherwise empty time, waiting time, is made full with consumer time, momentary fixes of meaning-making. A man’s worth, then, is contingent on something else: in this case, a Guinness beer. The Guinness brand bestows this resignified worth; this branding feeds a familiar narrative of branded Black bodies in the capitalist economy.

In 2008 Côte d’Ivoire was in the sixth year of a civil war that had split it into a rebel-held north and a government-controlled south. Already in its third decade of precipitous economic decline, the war exacerbated la crise (the crisis), justified the grounded economy, scared away much of the French and other expatriate populations who had long monopolized the inchoate business sector, and swelled an already strained urban labor market with displaced persons from the hinterland. Once the “Paris of West Africa,” Abidjan had become a decadent city, decadent in the double sense of the excessive indulgence the state lavished on the city center during its heyday and in the dilapidated condition of the majority of its urban space, constituted not by the planned colonial city but by the quartiers populaires.

This was a time when, by official counts, three-quarters of Abidjan’s four million residents were self-employed informally, earning their keep through luck and a hustler’s sensibility. Under the Guinness billboard worked vendeurs ambulants, or mobile street vendors. Concentrated, with no shortage of irony, around the Jardin Bourse du Travail, these vendors sold inflatable balls, car mats, camcorders, toilet paper, phone recharge cards, and other assorted bric-a-brac to motorists stalled in rush-hour traffic. As if to garner some dignity out of their uncertain status, the Guinness billboard offered an alternative possibility, an imaginary that reflected the shifting occupational realities and aspirations of Abidjanais men during a time in which finding a steady job was as unlikely as striking media stardom. In this imaginary established professionals rub shoulders with the new figures of the crisis economy: equivalent, then, are the pilot and the DJ, the athlete and the mechanic, the businessman and the street vendor. What they have in common—what makes them all great—is a Guinness in their hands. Here, Guinness has explicitly invoked greatness outside of wage labor, a realm demarcated by the colonial project.

This greatness was also rooted in the history of conquest. The imperial mission sought out foreign possessions not only as a source of land and labor but also as a market for European products. Undergirding this mission was a civilizational narrative that portrayed the consumption of foreign goods as Africans’ path up the gilded evolutionary staircase. In late capitalism, a time when the reality of permanent contraction surpasses the anticipatory moment of an expanding wage economy, incorporation of the world’s “bottom billion” renders proof of its triumph. An entrepreneurial-by-necessity, petty consumer class emerges as capitalism’s final frontier. Supplanting the promise of wage labor under a regulated, planned economy, every man is now free to achieve greatness, making and spending on his own accord. His capacity to do so is a test of his self-worth.

The Guinness advertisement extolled a vision of corporate empire and citizen-consumer. Yet residuals of other imperial etchings coexisted in this space. Pont Général de Gaulle, the quartier Treichville, the name Côte d’Ivoire: all marked Abidjan as a bulwark of Françafrique, solidified through the extractive and exploitative relations of metropole and colony. These etchings overlaid different eras in the continuous story of racial capitalism, eras that differentially incorporated Black men into processes of production, consumption, and commodification. The story of Abidjan is a story of racial capitalism told in the exaggerated hierarchies of work and in the racialized imaginaries that these hierarchies produced as men sought survival and status. During the interregnum, the miracle-turned-mirage that became known as la crise, imaginaries circulated in lieu of probable expectations. These imaginaries bore the legacies of Black men’s incorporation into racial capitalism, as would-be workers and would-be consumers in a modern economy—and in an enduring relationship to commodification as value.